Rows: 120

Columns: 24

$ series <dbl> 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2,…

$ baker <chr> "Annetha", "David", "Edd", "Jasminder", "Jon…

$ star_baker <int> 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0,…

$ technical_winner <int> 0, 0, 2, 0, 1, 0, 0, 0, 2, 0, 1, 2, 0, 1, 1,…

$ technical_top3 <int> 1, 1, 4, 2, 1, 0, 0, 0, 4, 2, 3, 5, 1, 1, 2,…

$ technical_bottom <int> 1, 3, 1, 2, 2, 1, 1, 0, 1, 2, 1, 3, 2, 6, 3,…

$ technical_highest <dbl> 2, 3, 1, 2, 1, 10, 4, NA, 1, 2, 1, 1, 2, 1, …

$ technical_lowest <dbl> 7, 8, 6, 5, 9, 10, 4, NA, 8, 5, 5, 6, 10, 8,…

$ technical_median <dbl> 4.5, 4.5, 2.0, 3.0, 6.0, 10.0, 4.0, NA, 3.0,…

$ series_winner <int> 0, 0, 1, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0,…

$ series_runner_up <int> 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0,…

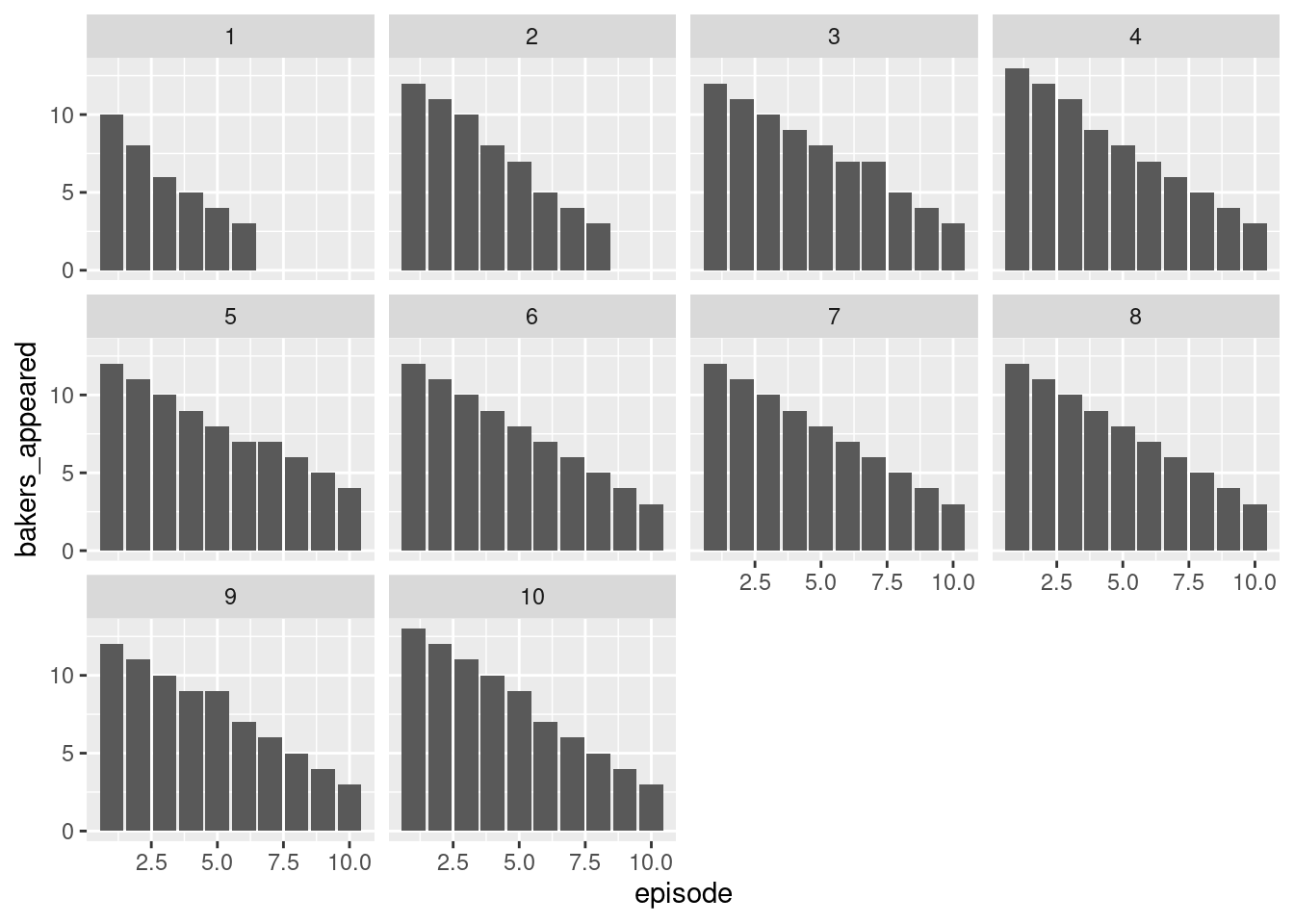

$ total_episodes_appeared <dbl> 2, 4, 6, 5, 3, 1, 2, 1, 6, 6, 4, 8, 3, 7, 5,…

$ first_date_appeared <date> 2010-08-17, 2010-08-17, 2010-08-17, 2010-08…

$ last_date_appeared <date> 2010-08-24, 2010-09-07, 2010-09-21, 2010-09…

$ first_date_us <date> NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA,…

$ last_date_us <date> NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA,…

$ percent_episodes_appeared <dbl> 33.33333, 66.66667, 100.00000, 83.33333, 50.…

$ percent_technical_top3 <dbl> 50.00000, 25.00000, 66.66667, 40.00000, 33.3…

$ baker_full <chr> "Annetha Mills", "David Chambers", "Edward \…

$ age <dbl> 30, 31, 24, 45, 25, 51, 44, 48, 37, 31, 31, …

$ occupation <chr> "Midwife", "Entrepreneur", "Debt collector f…

$ hometown <chr> "Essex", "Milton Keynes", "Bradford", "Birmi…

$ baker_last <chr> "Mills", "Chambers", "Kimber", "Randhawa", "…

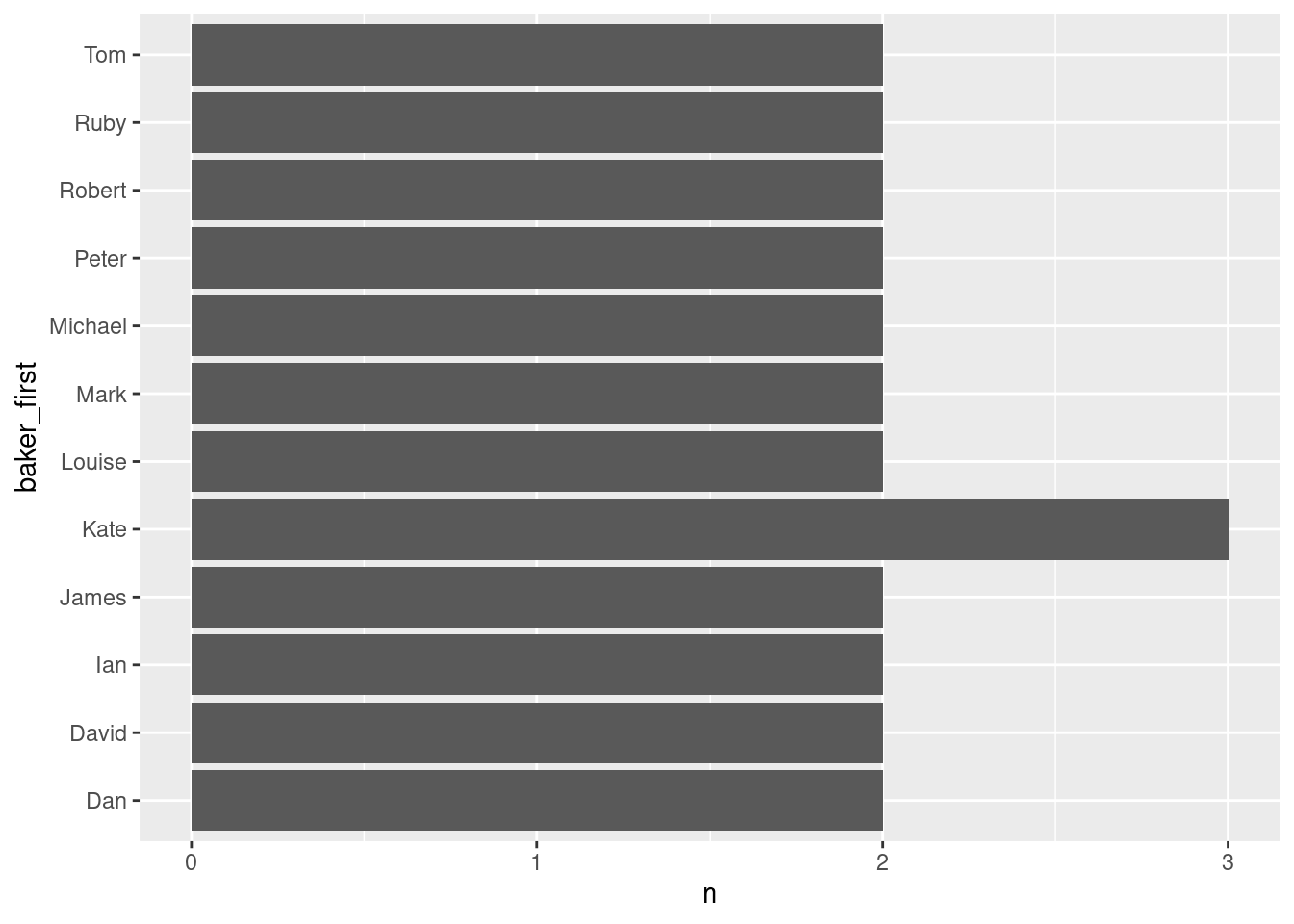

$ baker_first <chr> "Annetha", "David", "Edward", "Jasminder", "…